The Price-Negotiation Game is different from the quantity-pledging game, mainly because there is a single common price that will apply to all countries. If you could raise the price, it would cost you money, just like if you pledge to abate more. The difference is that if your price goes up, everyone else must set a higher price and abate more. That is not true in quantity-pledging negotiations.

- With your own cap, you lose money if you show altruistic “ambition.”

- With a higher common price, you gain more than you lose.

It doesn’t take ambition — only self-interest — to agree to a higher price. This is why a common global price treaty can be stronger than a Kyoto-style treaty.

Partial Carbon Pricing in Action:

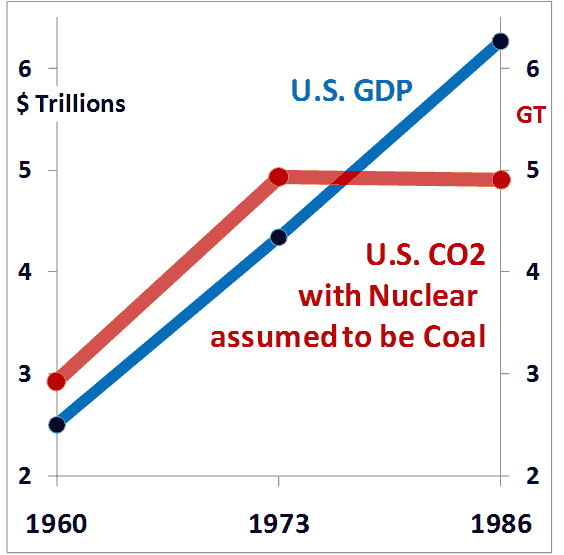

Note that emissions are calculated by assuming nuclear plants emit as much CO2 as coal plants. This eliminates the possibility that the flattening of emissions was due to new nuclear plants, as some have claimed. GDP is measured by the left axis and it was largely unaffected by the high carbon price imposed on gasoline. Remember that gasoline accounts for less than half of CO2 emissions.

Can a price be as strong as a cap?

Yes. This is indisputable because a cap only works by creating a carbon price. If a certain cap causes the carbon-permit price to average $30/t, and a tax sets the carbon price at $30/t, the two policies will have the same effect. No consumer or businessman takes action because a cap is set at X million tonnes, but only because that cap makes it costly for her to emit carbon.

In fact, the EU is so upset, in Jan 2015, with the price uncertainty caused by its ETS cap that it tried (unsuccessfully) to implement a “market stability reserve” of permits, which would periodically adjust the cap to produce a reasonably stable price. In other words, it would almost turn the cap into a tax. (Financial Times, Guardian) Caps and prices do the same thing, but caps cause much more (price) uncertainty for business.

How can a price hit a 2° target?

How can you keep your car going 60mph up-hill and down, with a pedal that only directly controls gasoline to the carburetor and not speed. We all know that’s easy — watch the speedometer and adjust the gas accordingly.

It works the same for controlling global temperature. Watch the temperature and control emission accordingly. If we are setting price there’s an extra step, but the principle is the same — watch your emission and adjust the price accordingly, but then check if your emissions are good for hitting your temperature target.

It turns out that the easy part is adjusting price to control emissions because we can see how we are doing every year. The hard part is figuring out what emissions level will hit a particular price target. So using price instead of the quantity of emissions doesn’t complicate the problem much at all.

Thinking we can set the right 80-year emission path today and run on autopilot forever is a glaring error in policy design. Many adjustments will be needed as we see how well we do and how the climate responds.

Don’t we need more than a price?

Yes. The negative externality of emissions is not the only market failure. Two other major failures are the under-rewarding of basic research and the externalities of land-use change. Consequently, we need a major increase in energy research funding and special policies for land use. There is no conflict between these and carbon pricing.

There are also other, smaller problems that require regulations. But regulations often have unintended consequences, so these should be designed cautiously.